This is a really lovely article about my talk to Polam Hall School in Darlington a couple of weeks ago. See here, and there’s a cute picture of some of the kids from the various local Darlington schools who were invited too.

Author: admin

2 space talks for schools this week

It’s been a busy outreach week for me. I started out on Monday travelling up to Darlington to visit the Polam Hall School where I’d been invited to speak to their pupils (there’s a press release here about my visit). This visit was organised by PHOSA which is the alumni association at the school. I hadn’t been to Darlington since I was last stuck there in the train station for a few hours many years ago after my train broke down when I was on my way back to Durham where I was studying for my undergraduate degree. This visit was, thankfully, much more pleasant. On Tuesday morning I was lucky enough to take 2 different classes (one geography and one science) where I spoke to the pupils about the meteorites that I’d carted with me (even the heavy ones) all the way from Milton Keynes. There were lots and lots of questions, some of them quite funny such as ‘Where does your poo go in space?’ when I told them that if they wanted to travel to Mars that it might take a few years (not that I wanted to put them off being astronauts of course)! I then did a talk in the afternoon in the school’s theatre entitled: ‘Ashes to Dust: A tour through space and time with Dr Natalie Starkey’. It was lots of fun and involved around 350 pupils from all the local Darlington schools. The meteorites were, once again, very popular at the end! Even the teachers wanted to hold a piece of Mars…who could resist.

Then today I’ve travelled up to Peterborough to speak to 100 7-11 year olds at Orton Wistow Primary School. They were a delightful group and had all done their homework so seemed to know a lot about space already. There was even one boy who managed to describe exactly what the Rosetta mission is going to do, I was very impressed indeed. This event was part of the Peterborough Children’s University charity which seems like a great idea to me. The kids follow a number of modules and then get to graduate with a ceremony at the end so they start to understand what university means and what it might do for them. Hopefully I encouraged a few of them today to think about science as a career. The teacher at the school had got the children excited about my talk (by showing them clips of me on TV) which resulted in them thinking I was some kind of celebrity and so they wanted my autograph at the end (see pic above)…and even a hug. Well, that was a nice way to end a talk, maybe scientific conferences should introduce hugs?? I also got some beautiful thank you flowers so it was a lovely lovely day overall.

Then today I’ve travelled up to Peterborough to speak to 100 7-11 year olds at Orton Wistow Primary School. They were a delightful group and had all done their homework so seemed to know a lot about space already. There was even one boy who managed to describe exactly what the Rosetta mission is going to do, I was very impressed indeed. This event was part of the Peterborough Children’s University charity which seems like a great idea to me. The kids follow a number of modules and then get to graduate with a ceremony at the end so they start to understand what university means and what it might do for them. Hopefully I encouraged a few of them today to think about science as a career. The teacher at the school had got the children excited about my talk (by showing them clips of me on TV) which resulted in them thinking I was some kind of celebrity and so they wanted my autograph at the end (see pic above)…and even a hug. Well, that was a nice way to end a talk, maybe scientific conferences should introduce hugs?? I also got some beautiful thank you flowers so it was a lovely lovely day overall.

Rosetta ESA swag arrived!

There was a rather exciting delivery for me this week as you’ll see from the above picture. This was a pallet delivered from ESA (European Space Agency) for the Catch A Comet Royal Society Summer Exhibition stand. We got lots of cool stuff which we’ll be giving away to our visitors (but you might have to answer a few questions on comets to get a freebie)! The sports water bottles (see below) are awesome, I’ve already started using mine, but we also have pin badges, stickers and posters, all with Rosetta logos and cool pictures.

There was a rather exciting delivery for me this week as you’ll see from the above picture. This was a pallet delivered from ESA (European Space Agency) for the Catch A Comet Royal Society Summer Exhibition stand. We got lots of cool stuff which we’ll be giving away to our visitors (but you might have to answer a few questions on comets to get a freebie)! The sports water bottles (see below) are awesome, I’ve already started using mine, but we also have pin badges, stickers and posters, all with Rosetta logos and cool pictures.

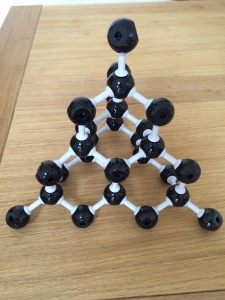

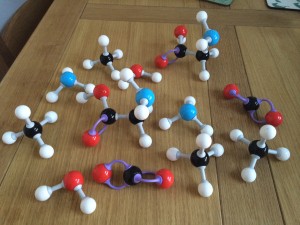

I also spent a few evenings making the Molymod molecules for the comet sculpture we’ll install at the exhibit. Here’s a few of the ones I made so far…can you name them? Clue: the first one is the hardest natural substance. Second clue: They’re all found in comets.

I also spent a few evenings making the Molymod molecules for the comet sculpture we’ll install at the exhibit. Here’s a few of the ones I made so far…can you name them? Clue: the first one is the hardest natural substance. Second clue: They’re all found in comets.

New logo for Catch A Comet at The Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition

I made a prototype logo a while back (you can see it here on my previous blog post) but it was clearly quite ‘naïve’, as my high school art teacher might have said. Anyway, we have a beautiful new one now that was made by Dr Ben Dryer in my department. He clearly has much better logo designing skills than me! Thank goodness!

Picking pieces of comet dust + Royal Society Summer Science website live!

Well it’s certainly been a busy month as I’ve been preparing my new comet dust samples and doing lots of planning for the Royal Society summer science exhibit.

The comet dust lab work involves manipulating 10 micron-sized pieces of comet from a glass slide to a gold foil mounted on an aluminium stub using a tungsten needle mounted on a high tech micromanipulator on a high powered optical microscope. Phew, that’s hard to describe! I’ve managed to move 14 of the particles so far and so I have plenty to be getting on with for the next phase of analyses which includes SEM and Raman to look at the elemental chemistry and organic material.

For the Catch A Comet exhibit for the Royal Society I’ve been in discussions with the comet sculpture makers Wild Flag Studios and they are coming back to me with some designs soon. Very excited to see what they come up with. There’s been a mountain of other little things to do as well and as soon as I’ve finished something I find another thing that needs doing!

Oh, and if you’re interested in the real science coming out of the Rosetta mission then the scientists running the Ptolemy instrument have set-up this nice little blog to tell us all about what they’re doing on a daily basis as we approach and land on comet 67P.

The Royal Society Summer Science Exhibit website is now live (see here) and you can watch the the film we made to explain the science behind the exhibit here or above.

Lunar Planetary Science Conference 2014, Houston.

It’s been a little while since my last update but once again that’s because life has been busy and this was mostly related to the LPSC 2014 conference that I attended last week over in Houston, Texas. It was my 4th time at this conference and the 3rd time I’ve presented a talk there. This year my talk wasn’t scheduled for Friday afternoon which was really great because it meant I got it out of the way on Tuesday and so I could relax and enjoy the rest of the week not worrying about my talk. I think my talk went well though, I got lots of positive feedback from other scientists and lots of interest in the data that I presented about the comet dust I’d analysed. This particular piece of comet dust forms a large component of a paper I’ve just submitted too so I’m pleased scientists are interested in it.

The conference itself was really great as usual. On the first Sunday I went to a special session about the Moon and I got to hear two Apollo astronauts speak (Dave Scott and Harrison Schmitt). They were both so inspiring to listen to and we heard some really funny anecdotes about the Moon. How lucky these guys are to have experienced that. I wonder if anyone in my lifetime will ever set foot on the Moon, or any other planets, again. I sadly think not! What did interest me though was how much geology training these guys went through. I’d assumed they were ‘just’ amazing test pilots (apart from Schmitt who was a geologist of course) but it seems that their geology training on the Apollo programme really instilled a passion in them for the rocks. Well, who wouldn’t get excited about rocks?! 😉

Anyway, future Moon landings set aside, there’s plenty of great space science still going on and the LPSC conference just confirms how active the science community is and how many different and new areas we’re finding to exploit to find out more about the Solar System in which we live. I can’t wait for next year but I guess this means I better get back to the research now so I have something new to present.

So, this week has been spent getting over the jet lag and lab planning for the NanoSIMS. Unfortunately this instrument doesn’t run itself and it’s due some more feeding now so we’ve been planning the projects that need time on it over the next few months. Some new users get to experience the ‘joy’ of running the NanoSIMS soon so I hope they get some great data soon to kick off the real analysis phase of their projects. Looks like I’ll be back on the instrument Monday running tests in preparation to analyse the Hayabusa asteroid samples!! No rest for the wicked 🙂

Catch A Comet – Rosetta at The Royal Society

I’ve gone quiet for a fair few weeks after all the excitement of the Rosetta wake-up…and thank goodness that it did manage to wake up or else the start of 2014 would not have felt very positive. So what have I been up to since? Well, we’ve had our Rosetta proposal selected for a place at the Royal Society Summer Exhibition (2014 website live in April) which has kicked me into a frenzied spin of activity including lots of planning meetings and headaches over how we’re going to bring all our plans together. It seemed so simple to propose amazing exhibit designs in the proposal but now we have to make it happen! I’ve set up a twitter feed that will slowly start to document our activity of making the exhibit happen (@CatchAComet) and Leah (my counterpart planner at Imperial) has set up a Catch A Comet Tumblr for us too.

The exhibition is on from June 30th to July 6th in London and is open to the public for a lot of the time. There’s about 25 exhibits taking part from all areas of science. It’s going to be awesome fun. Oh, and we plan to take down the cool Rosetta lander model currently at the Open University…although our first task is working out how to get it through the doors of the Royal Society because they are very narrow (and apparently we’re not allowed to remove them to fit the model through, who’d have thought?)!

I had a go today at drawing a logo that we can use as our ‘branding’ (if I give it a posh name it makes it seem better), see above. It’s subject to change because the team haven’t seen it yet but I quite like its naïve cartoon-style (my art teacher at school always told me my drawings were a bit ‘naive’, I think she was trying to find a nice way to say they were rubbish)!

But that’s not all I’ve had going on…oh no, the life of a scientist is rather more manic than this! I’ve been helping get my students paper (on the earliest solids to form in the Solar System) in order to go back to the journal after review (fingers crossed its accepted now) and I’ve been finishing my own comet dust paper (a new one, yay!). I hope to submit it this week and I spent a lovely afternoon today drawing a big schematic diagram in CorelDraw to help illustrate my model for how comet’s formed in the early solar nebula. I’ve passed it by my boss now so I’ll see what he thinks to it…again, cartoon-style seems the way forward.

Oh, and the other thing I’ve been doing is lots of NanoSIMS lab work (I just can’t get away from that instrument). Some of this work involved measuring the hydrogen isotopes in some comet dust for a collaboration I have going on. The results from 4 tiny pieces of dust are all very different which just confirms once again how variable this dust is, and therefore why it’s so exciting to analyse…you just never know which bit of the Solar System you’re going to get 🙂

Wake Up Rosetta!! Part 2

We’re sitting/pacing nervously at the Open University waiting for news from the Rosetta spacecraft about whether it’s managed to wake up from its 2 year deep space slumber. Hopefully the alarm clock went off at 10am but no news is expected until 1600 to 1800 GMT. In the meantime, we have Sky News here getting lots of live interviews with many of the Ptolemy instrument team (including me)! And various other news channels are getting interested now too. I was on BBC Breakfast this morning and a link to the piece with the BBC Science reporter Rebecca Morelle is here.

Wake up Rosetta!!

Here’s my new article on The Conversation website about the waking up of the Rosetta spacecraft on Monday!! Everyone keep their fingers (and toes) crossed!

https://theconversation.com/uk

Sleeping spacecraft Rosetta nearly ready to wake up

By Natalie Starkey, The Open University

The Rosetta spacecraft is due to wake up on the morning of January 20 after an 18-month hibernation in deep space. For the past ten years, the 3-tonne spacecraft has been on a one-way trip to a 4km-wide comet. When it arrives, it will set about performing a manoeuvre that has never been done before: landing on a comet’s surface.

The spacecraft has already achieved some success on its long journey through the solar system. It has passed by two asteroids, Steins in 2008 and Lutetia in 2010, and tried out some of its instruments on them.

Because Rosetta’s journey is so protracted, preserving energy has been of utmost importance, which is why it was put into hibernation in June 2011. The journey has taken so long because the spacecraft needed to be “gravity-assisted” by many planets in order to reach the necessary velocity to match the comet’s orbit.

When it wakes up, Rosetta is expected to take a few hours to establish contact with Earth, 673 million km away. The scientists involved will wait with baited breath. Dan Andrews, part of a team at the Open University who built one of Rosetta’s on-board instruments, said, “If there isn’t sufficient power Rosetta will go back to sleep and try again later. The wake-up process is driven by software commands already on the spacecraft. It will wake itself up autonomously and spend some time warming up and orienting its antenna towards Earth to ‘phone home’.” If multiple attempts fail to wake Rosetta, it could mean the end of the mission.

Rosetta should reach comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in May 2014, at which point it will decelerate to match the speed of the comet. In August 2014 Rosetta will enter orbit around the comet to scout 67P’s surface in search of a landing spot. Then, in November 2014, Rosetta’s on-board lander, Philae, will be ejected from the orbiting spacecraft onto the surface of the comet. There are a lot of things that need to come together perfectly for this to go smoothly, but space endeavours are designed to charter unknown territories and Rosetta will be doing just that.

If Rosetta manages this successfully, it will make history as the first spacecraft to land on the surface of a comet. Success is by no means assured, as scientists have no idea what to expect when Rosetta arrives at the comet. Will the comet’s surface be icy, soft, hard, or rocky? This affects what kind of landing the spacecraft can expect, and whether it will sink into the comet or bounce off. Another problem is that comet 67P is small and has a weak gravitational field, which will make holding the spacecraft on its surface challenging, even after a successful landing.

At a cost of €1 billion (US$ 1.36 billion) it is important we get some value for our money with this mission. To ensure we do, Rosetta was designed to help answer some of the most basic questions about Earth and our solar system, such as where water and life originated, even if the landing doesn’t work out as well as we hope it will.

Comets are thought to have delivered some of the chemicals needed for life, including water to Earth, and possibly other planets. This is why comet ISON, which sadly did not survive its close encounter with the Sun, had created excitement among scientists. If it had survived, it would have been the closest scientists could get to a comet with modern instruments.

Comet ISON’s demise means Rosetta is more important than ever. Without measuring the composition of comets, we won’t fully understand the origin of our planet. Comet 67P is thought to have preserved the very earliest ingredients of the solar system, acting as a small, deep-freeze time capsule. The hope is it will now reveal its long-held secrets to Rosetta.

Andrews said, “It will be the first time a spacecraft will approach a comet and actually stay with it for a prolonged period of time, studying the processes whereby a comet ‘switches on’ as it approaches the Sun.”

Once on the comet’s surface, the Philae lander will deploy instruments to measure different forms of the elements hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen in the comet ice. This will allow scientists to understand the composition of the water and organic components that were collected by the comet 4.6 billion years ago, at the very start of the Solar System.

All this depends on whether Rosetta wakes up on Monday. If it does, like the 2,000-year old stone it has been named after, it will reveal a world that has long fascinated humanity.

Natalie Starkey receives funding from the Science and Technology Facilities Council. She is affiliated with The Open University.

![]()

This article was originally published at The Conversation.

Read the original article.

Another new article I wrote for The Conversation website on comets and asteroids

Looks like a comet but feels like an asteroid? That’s wild!

By Natalie Starkey, The Open University

Comet ISON’s fate has left many sad. For the public, the comet could have made for a spectacular view in December. For scientists, it would have been a chance to learn more about these mysterious bodies. But why are comets mysterious? And what really are they? Some recent missions are beginning to answer that question

In 2006 the NASA Stardust mission returned to Earth with the first samples collected directly from a comet. What scientists discovered when they analysed the samples was not what they were expecting. The results challenged many commonly-held assumptions about the composition of comets and asteroids, as well as the formation of the solar system as we know it today.

Before this mission, scientists had always characterised comets and asteroids as completely different. Asteroids make frequent deposits on Earth in the form of meteorites and are thought to have formed in the inner solar system, close to the sun. They contain rock minerals that formed in high temperatures early on in solar system history – more than 4.5 billion years ago. Their orbits are generally circular.

Comets, on the other hand, are less-frequent visitors from the outer solar system. They are often called dirty snowballs and are believed to act as time capsules from the deep freeze of the solar system, containing the primary dust and gases from which everything we can touch and smell began. Comets glow and produce a tail of gas and dust when they pass through the inner solar system because the sun’s heat causes frozen gases within them to sublime. Their orbit is different to that of asteroids, being generally more elliptical.

The Stardust mission collected grains from the tail of comet 81P/Wild2. Analysis of these grains revealed them to be high-temperature rock minerals, indistinguishable from those commonly found in asteroids, their presence indicated an inner solar system origin. But 81P/Wild2 looks, smells and acts just like a comet. And, having been wrenched from its more distant orbit to one in the inner solar system by the gravitational pull of Jupiter in 1974, its orbit classified it as a comet.

The big question is: how can a comet contain minerals formed in the inner solar system when it is supposed to have been formed some 30AU away from the sun, where AU is the distance from the Earth to the sun, and its surroundings are as cold as -200°C?

This question has thrown space scientists into disarray, showing that classic solar system formation models that have been relied on for many years do not square with the evidence in these samples. Unfortunately only one comet has been sampled directly of the trillion or so that are estimated to exist.

Even without real rock samples returned to Earth, astronomers have recently used an infrared telescope to study an asteroid remotely. It is called 24 Themis and is located in the outer part of the main asteroid belt, between Mars and Jupiter. It was found to contain water-ice, an unexpected component in an asteroid and something that would normally help to classify it as a comet. Also, asteroid P/2013 P5 was observed by the Hubble Space Telescope in September this year to have six cometary-like tails, even though it has an asteroid-like orbit. These results obtained remotely would not be understood so well without the Stardust mission.

So where does this leave us and why does it matter? The current thinking is that the two extremes of composition do exist. Some asteroids are true asteroids – they contain only material formed in the inner solar system and no water ice. Conversely some comets are true comets – they contain only outer Solar System material. But the samples obtained from 81P/Wild2 and remote sensing of other solar system objects highlights that solar system models must account for a continuum of compositions from asteroid to comet.

Many elements of the universe remain a mystery. For instance, it is still unclear if water and organic material were delivered to Earth by comets or asteroids. But perhaps more Earthly desires will drive research in this area. One that no longer seems science fiction is the mining of space objects for their precious metals.

Before anyone goes to the expense of sending a mining mission to an asteroid, they will want to check first that it contains the metals they require. If comets have such metals too, then perhaps asteroids won’t be the only potential mines we have.

Natalie Starkey receives funding from the Science and Technology Facilities Counci. She is affiliated with Planetary and Space Sciences at The Open University.

![]()

This article was originally published at The Conversation.

Read the original article.